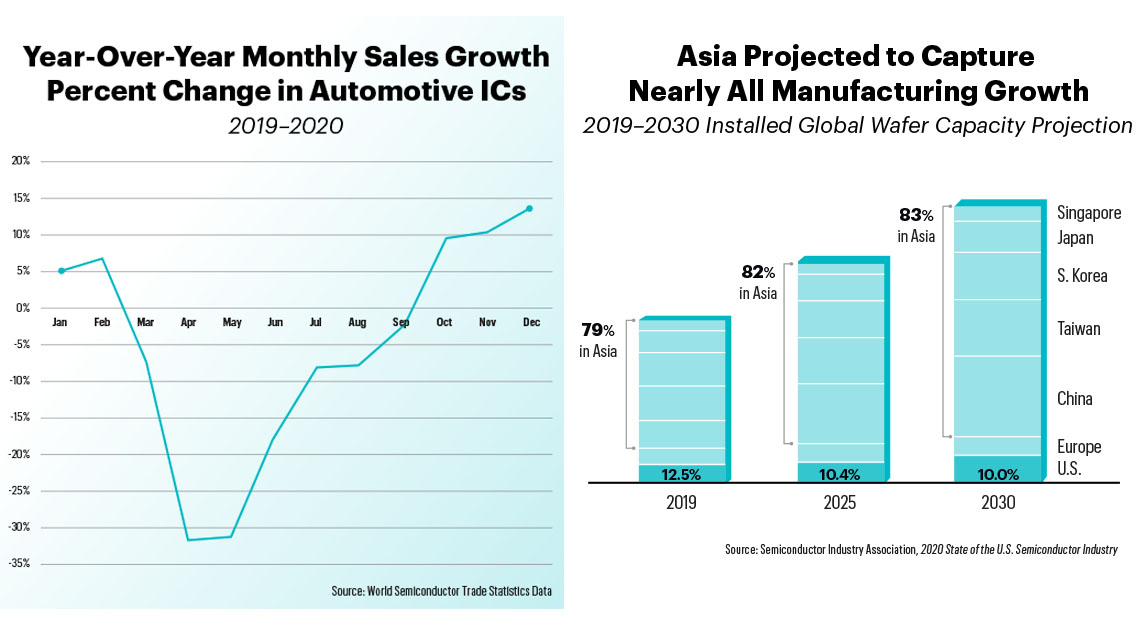

When COVID hit, according to World Semiconductor Trade Statistics data, automobile original equipment manufacturers (OEMs) reduced orders by over 30% year-over-year in April and May 2020.

This reduction created ripple effects. Notably, production capacity at chip fabrication facilities (fabs) were scooped up by companies building technology supporting the thriving stay-at-home economy during the pandemic.

Meanwhile, automobile OEMs were preparing for a slowdown, but events unfolded unpredictably. Spending rebounded in the second half of 2020 and auto sales climbed ahead of forecasts.

Accordingly, OEMs re-engaged their channels, attempting to shore up inventory levels, but were unsuccessful. Because of this, vehicle production slowed or stopped. Long lead times for new orders (14 to 26 weeks for delivery) and the lack of available chips, sub-components and capacity at contractor fabs were major contributing reasons. For example, GM shuttered plants in Kansas, which manufactures the Cadillac XT4 and Chevrolet Malibu, and Ingersoll, Ontario, which makes the Chevrolet Equinox.

And in February, Ford cut production of the F-150 pickup truck. All told, market research firm, Strategy Analytics, expects 2021 global vehicle production output to decline by 2.2 million units because of the chip shortage, with a loss of $7.5 billion of system demand across all electronic vehicle systems.

The automobile industry highlights the critical dependence electrical systems and technology products have on semiconductor chips.

The global market for the semiconductor industry is escalating rapidly. It is currently projected to reach $469 billion in 2021, increasing 8.4% from 2020. Despite its enormous market

size, the reported automobile chip shortage highlights another and more profound concern, the U.S. reliance on offshore chip manufacturers for supply.

The U.S. is a leader in semiconductor innovation in several categories, accounting for 47% of the global sales market share and 65% of the global fabless market according to the Semiconductor Industry Association (SIA). However, when it comes to manufacturing capacity, the U.S. is losing its edge, with a 12.5% share of global production in 2019 forecasted to drop to 10% by the end of 2030. This is a deepening concern for national security, particularly if chip shortages stymie the advancement of new U.S. technological innovations.

Over the past decade, the U.S. has been at the forefront of technological innovations such as the Internet of Things (IoT), artificial intelligence (AI), and “smart” consumer technology products. Other sectors and technologies driving demand include:

CTA research forecasts U.S. consumer technology hardware shipments will reach 1.2 billion units and generate $264 billion in wholesale revenue by 2024

Semiconductor capacity (manufacturing of wafers per month) is expected to rise by 56% from the current installed base by 2030, but as of June 2020, 50% of this new capacity was not yet planned. Also, today 73% of the worldwide chip production capacity resides in eastern Asia (Taiwan, South Korea, Japan and China), representing substantial risk to U.S. OEMs and to global chip supplies. Despite Intel’s announcement on March 23, 2021 to construct two new fabs in Arizona, as of June 2020, only 6% of new fabs “in development” were slated to reside in the U.S., leaving significant opportunity to fill the remaining unplanned gap.

However, constructing new production facilities is both costly and time consuming taking between three to five years. For example, TSMC is expected to begin construction of its Arizona plant this year at a cost of $12 billion, but not output chips until 2024. Intel’s two fabs in Arizona are estimated to cost $20 billion.

The long-term challenges associated with growing the U.S. semiconductor supply are apparent, but in the short-term, immediate demand for chips remains high. Industry experts expect shortages to last at least until the end of 2021. With new chip orders placed two to four quarters in advance and with long delivery times, meeting existing demand is a lengthy process. The implications of the chip shortage on this year’s product shipments are less certain, but it is possible that the production of gaming consoles, smartphones, and other computing products will be cut from initial levels.

At a macro-level, the pandemic highlighted weaknesses in the U.S. technology ecosystem, specifically, dependence on overseas wafer and fab companies. And in an environment where technology expansion is irrefutable, the supply of semiconductor chips must be solidified. CTA will continue to track events and the evolving market conditions to understand the implications of this critical issue.

I3, the flagship magazine from the Consumer Technology Association (CTA)®, focuses on innovation in technology, policy and business as well as the entrepreneurs, industry leaders and startups that grow the consumer technology industry. Subscriptions to i3 are available free to qualified participants in the consumer electronics industry.