IT departments were working overtime to enable our remote national workforce. Something had to give. Verizon’s Mobile xSecurity Index 2021 found that 45% of respondents said that their companies had sacrificed mobile security to just “get the job done.” In the same survey, 48% of those who made some kind of sacrifice on cybersecurity said that one of the reasons was dealing with the COVID-19 crisis. These numbers illustrate how much pandemic-related changes in the nature of work have led to increased vulnerability for companies and their employees.

The main concerns today are about data theft, ransomware and denial of service attacks.

Security folks refer to a data breach or data theft as “data exfiltration”: “theft or unauthorized removal or movement of any data from a device.” Security of enterprise systems has gotten better over the years, but hackers can take a small opening and exploit it to get a little more access, and then from there a little more, and so on to the full breach.

Data theft was one of the first goals of hackers (along with theft of services, such as long-distance phone calls). Over time, hackers have become more ambitious. In 2013, Target was the subject of a data breach that the company announced could impact tens of millions of customers. It was the largest breach of its kind at the time, but Target is by no means the only major retailer or business that has had data stolen, and since that time LinkedIn, FaceBook, Yahoo!, Starwood (Marriott), Twitter, Experian, Equifax and others have been victimized at large scale.

The SolarWinds exploit was just such a situation. Hackers sponsored by the Russian Foreign Intelligence Service (SVR) tapped into software that was used by many enterprises and federal agencies in the U.S. By attacking a supplier to companies rather than the companies themselves, the attackers were able to multiply the reach of the attack many times. When this sort of upstream attack occurs, it’s referred to as a supply chain attack.

Ransomware is another major threat in 2022. Like data exfiltration, ransomware starts with hackers gaining access to enterprise (or even consumer) systems. Once “in”, the malware will encrypt the system’s hard disk drives. Typically an email or pop-up tells the user that their system is encrypted and demands payment, usually in bitcoin. The U.S. Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) discourages paying up. It notes, “Paying a ransom doesn’t guarantee you or your organization will get any data back. It also encourages perpetrators to target more victims and offers an incentive for others to get involved in this type of illegal activity.” Ransom payments tend to fuel illegal activities and prop up dictatorships. In the latter case North Korea’s military has been accused of ransomware attacks to finance the sanctioned regime.

Like a biological virus, ransomware is evolving. The first and most obvious trick the criminals learned was to stay inside the infected system, even after payment. That way they can continue to sift through corporate databases or shut systems down again for another payment.

Possibly the most innovative new technique is for ransomware operators to offer payment to employees to load the malware themselves. This is the equivalent of a warring feudal lord bribing a guard to open the gates of the fortress.

The third major concern is the “distributed denial of service attack”, or DDoS. To “deny service” on the internet, a massive flood of useless traffic is sent to confound the hapless webserver or other internet system. Overloaded with inbound rubbish, the internet system cannot support legitimate requests, like showing a favorite web page.

Today these attacks are done with a slew of devices worldwide, devices that have been hacked for this purpose. The “distributed” nature of the attack turns the small-scale technique into a DDoS. Hackers used to compromise individual computers in order to use them for the source of such traffic. But now the internet of things (IoT) is also a source of computing power for these DDoS attacks, since many IoT devices are built with a small but powerful computing platform and an operating system such as Linux.

DDoS attacks are on the rise. Already a problem in 2019, DDoS defense specialty company CloudFlare observed for 2020, “After doubling from Q1 to Q2, the total number of network layer attacks observed in Q3 doubled again — resulting in a 4x increase in number compared to the pre-COVID levels in the first quarter.” And the attacks are getting worse. In August, CloudFlare fended off a botnet-based DDoS attack that amounted to 68% of all web requests they see on average. This particular attack did not come from one particular place; in keeping with the “distributed” nature of DDoS, the attacking traffic originated in 125 countries around the world.

Government and industry leaders are concerned about these surging attacks, but there are other threats as well. The scenario of a lone hacker taking down the energy grid, or financial markets, or the telecommunications system is well known to movie goers. But real versions of these scenarios are very much on industry and government leaders’ minds. It’s important to protect our critical infrastructure, as we’ve seen with the Colonial Pipeline attack.

This challenge is a big one, but there is quite a bit of work being done. Government agencies are working with industry coalitions on multiple fronts. First, “critical infrastructure” has been a legally defined term since the Clinton Administration. It currently includes 14 categories including water and energy, information technology and telecommunications, agriculture and finance. These categories receive greater assistance with correspondingly greater responsibilities. After all, if you’re providing the nation with a service that, if crippled by a cyberattack, would have “a debilitating impact on security, national economic security, national public health or safety”, you should expect greater visibility and responsibility.

Consequently, industry leaders are working on cyber crisis scenarios and plans. The Council to Secure the Digital Economy’s Cyber Crisis: Foundations report lists a dozen major scenarios and details what action should be taken in each case.

The cloud can be safer for data, but it is not entirely fool-proof. First, a common reason cloud systems are hacked is incorrect configuration. Hackers have automated the scanning of cloud accounts, looking for access privileges mistakenly left to the equivalent of “public”. This is like a criminal at night, going from car to car in a parking lot, looking for one left unlocked.

If the attacker has a user’s email credentials, they can encrypt email messages. Files infected on a physical device—like a laptop—will still be infected if they are synchronized to cloud storage. Many attacks start with phishing attacks – the sending of emails for what appear to be legitimate purposes – to surreptitiously obtain user login credentials.

And the consumer technology industry is part of all critical infrastructure at this point. Agriculture, finance, energy, and all other sectors use computers, networking equipment and connected devices from the consumer side. A major botnet-based DDoS attack took down over 100 of the most popular websites in the U.S. and U.K. in 2016. The attack kicked off a significant public-private partnership effort led by the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST). This led to an entire framework built from industry and agency efforts: baseline security guidance for all devices, a parallel consensus guidance from industry, technical standards and conformity assessment programs—all traceable back to the NIST guidance.

CTA’s own standards development group, Technology & Standards, in operation since 1924, is part of this consensus framework. The Cybersecurity and Privacy Management committee developed ANSI/CTA-2088 (“-2088”) as a direct expression of the guidance in the earlier documents. Engineers and developers rely on industry consensus technical standards like -2088 to give them clear rules for development, and conformance groups use such standards to check to see if the device complies. Complying with standards like -2088 helps prevent IoT devices from being used as part of DDoS and ransomware attacks.

What happens in the event of a national cyber crisis? The Council to Secure the Digital Economy (CSDE) identified a dozen major scenarios that could potentially bring severe harm to the nation. The group identified how major stakeholders – ISPs, cloud service providers, software and hardware providers, and more – would need to come together to counter the attack. The scenarios include:

• DDoS Botnet Attack

• DDoS Server-based Attack

• Border Gateway Protocol (BGP) Hijacking

• Domain Name System (DNS) Hijacking

• Software Vulnerabilities: Open Source

• Software Vulnerabilities: Zero Day

• Hardware Vulnerabilities: Processor Architectures

• Injection of Malicious Code in Software and Hardware Components

• Destructive Malware

• Ransomware

• Advanced Persistent Threat (APT): Industrial Systems

• Cloud Provider Compromise

Ransomware, by its very nature, implies a financial incentive. Attackers demand payment for the key to decrypt corporate or consumer data. Companies don’t always pay, but Colonial Pipeline famously paid the equivalent of $4.4 million in a 2021 ransomware attack. And as mentioned earlier, hackers are now offering to pay the employees of a potential target for loading malware on their employer’s systems.

There also is a robust market for hacking services on the “dark web”. The dark web is a secretive part of the World Wide Web protected by special access software and used for illegitimate and illegal activities. Stolen data, in the form of personal information like credit card numbers, social security numbers and passwords, is for sale on the dark web.

Originally, gamers were the ones growing the DDoS attack market on the dark web. When some skilled player in another city is cutting down your favorite character, it’s possible to purchase a DDoS attack on that player. The flood of traffic slows their system response time, a phenomenon known as “lag”, and a laggy gamer’s avatar freezes on the screen, or moves slowly—easy to target and short-lived. Now DDoS attacks are for sale, averaging about $10 per hour of attack, depending on the size of the attack (how much traffic, in gigabytes per second, will be sent to the hapless victim).

For a start, it’s worth mentioning that everyone should be aware of good cyber hygiene practices. Forbes has a good list online.

And fortunately, consumer technology is getting more secure. “Smart firewalls” – like Akita, BitDefender, Cujo and Norton Core – can be installed between your internet service provider’s router and the rest of the devices in your home. Amazon has added end-to-end encryption for its Ring doorbell product, meaning that the video is secured between the smart doorbell and your cloud video storage. If you’re concerned about your email, there are services to encrypt it.

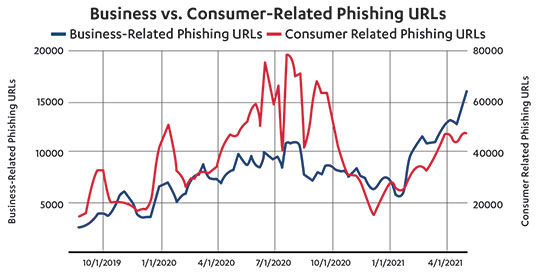

Business vs. Consumer-Related Phishing URL's

Business-Related Phishing URL's: 10/1/19: ~4000 | 1/1/20: ~7000 | 4/1/20: ~8000 | 7/1/20: ~9000 | 1/1/21: ~7000 | 4/1/21: ~16000

Consumer-Related Phishing URL's: 10/1/19: ~30000 | 1/1/20: ~50000 | 4/1/20: ~40000 | 7/1/20: ~60000 | 1/1/21: ~25000 | 4/1/21: ~50000

Besides personal protection, one might also consider the financial opportunities offered by investment in cybersecurity. With all the industry action and government focus on cybersecurity, it certainly sounds like a growth industry. It is, and in fact it’s easy to invest in cybersecurity. CTA curates the NQCYBER cybersecurity index for NASDAQ, and there are several exchange traded funds (ETFs) that derive from it:

ETF Name

Bloomberg Ticker

First Trust NASDAQ Cybersecurity ETF

CIBR:US

Betashares Global Cybersecurity ETF

HACK:AU

First Trust NASDAQ Cybersecurity UCITS ETF

CIBR:LN

|

ETF Name |

Bloomberg Ticker |

|

First Trust NASDAQ Cybersecurity ETF |

CIBR:US |

|

Betashares Global Cybersecurity ETF |

HACK:AU |

|

First Trust NASDAQ Cybersecurity UCITS ETF |

CIBR:LN |

|

ProShares Ultra Nasdaq Cybersecurity ETF |

UCYB:US |

As far as the overall threat level for consumers, the bottom line is that there are two areas of concern. First, consumers should be aware of threats to their personal information. Phishing is used extensively to attack corporations, but consumers get phishing emails too. The goal of a consumer phishing email is to get a consumer to click on malicious links that look like well-known social media brands, consumer banking and other popular consumer sites. This can expose personal information, especially credentials for logging in to sites—giving a malicious actor easy access to accounts.

During the pandemic shutdown, Palo Alto Networks found that consumer phishing attacks increased by roughly 100% from February 2020 to June 2020, as seen in the chart below. The message is definitely, “Think twice before clicking that link.”

Specifically, get in the habit of looking at the link address itself. Is the “domain name” (in the U.S., the last two parts) owned by a company you trust? A common trick is to put a familiar name into (non-critical) locations ahead of the domain name. The link “google.evilhacker.com” is not owned or controlled by Google. But “literallyanything.google.com” is owned by Google, as indicated by the “.com” domain, and anything there can be trusted on the same level as google.com. The same is true for link addresses ending in .org, .tech, .edu, etc.—however, note that a country-specific code like “.ca” (for Canada) may be added at the end (like “stuff.google.com.ca”).

Also—hopefully it goes without saying, but be doubly careful whenever you are asked for login credentials. Check the address bar and domain name for the same kind of “who owns this” test as described above.

Another area of concern for consumers is connected device compromise. Hackers take over smart devices in order to build networks of computing and internet power that they can command and control. These networks are called botnets and are one of the ways hackers create DDoS attacks. A compromised home device, like a printer, router or web camera, may act oddly. It’s no wonder, it’s under someone else’s control.

There are other concerns, including theft of data including camera video and banking credentials. It’s smart to secure your smart home.

And finally, if you’re attending CES 2022 January 6-10 in Las Vegas, make sure to check out the conferences. Privacy and cyber security will be important themes across multiple verticals in CES 2022 programming, such as the impact of cybersecurity on 5G. On that theme, one panel to check out is “Cyber Crisis Handling: Who You Gonna Call?” In this session, U.S. infrastructure cybersecurity experts from AT&T, Intel, Lumen and Oracle will talk about what to do in the event of a major cyberattack—their worst nightmare—and the consequent disruption of U.S. telecommunications and internet infrastructure.

Hackers have grown more bold, numerous and active. High-profile cyberattacks have become more common, and there are concerns about critical infrastructure. But there are quite a few efforts underway to push back, by industry working in partnership with government agencies, and there are some excellent proactive steps you can take to protect yourself as well.